Joe Biden’s campaign for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination flamed out after the revelation that he had cribbed lines from Neil Kinnock, then leader of the British Labor Party. He passed on the 1992, 2000, and 2004 races, becoming instead what is both generously and condescendingly called “an institution.” He presided over the disastrous Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings. He helped write the Violence Against Women Act. He authored a bipartisan authorization for the invasion of Iraq that fell somewhere between the actual policy the administration pursued and sanity. He appeared prominently in a New Yorker thumbsucker about “national security Democrats,” supposedly sober and hawkish voices in a party back-footed by the War on Terror. He proposed the partition of Iraq and tangled fruitlessly with Bush’s Supreme Court nominees over Roe v. Wade. He workshopped a “lion of the senate” rhetorical style that either didn’t work or didn’t stick. Already a bit of an anachronism before his under-funded and poorly-conceived 2008 presidential run, Barack Obama rescued him from a sunset era of humiliating respectability by naming him to the ticket.

If my memory serves, I was a little disappointed by the choice. But as the Number Two, Biden finally found a role that suited him. Freed from the need to orate, he was able very effectively to speak, hitting emotional registers his boss couldn’t reach. In his convention speeches—very good, certainly by the low standards for vice presidential nominees, and in 2016, better than the candidate’s own speech—he talked about his mother telling him to bloody the noses of bullies, and when he went into attack mode, he had a way of quieting the crowd down before really sticking in the rhetorical shiv. Rather than tangling with the smooth movement-conservative lawyers appointed to federal courts, he was put on stages opposite Sarah Palin and Paul Ryan, either of whom would have skittered off in a stiff breeze, and he handled them effectively with his dogged bluster. He was good at this.

When he got the top job, he was still good enough at it that we could all see why he got close enough to win in the first place. And he headed an administration that, admirers and detractors would have to agree, notched some unexpected policy gains. Even as he started to recede from public view—even as the approval ratings sank and stayed low, with his re-election numbers eventually following—his supporters assumed he could still pull something off.

That didn’t change until the debate, and while the voices coming out of his party shifted back and forth until he dropped out, nothing in his subsequent public performances indicated that he really had the old fire, the edge, whatever it is that bulled him past a dozen strong Democrats and Donald Trump and Paul Ryan and Sarah Palin. He had become undeniably smaller, more peevish, more self-centered and less apt to turn every rhetorical barb aimed at him into a story about what matters to “the American people” around their kitchen tables. As I watched the BBC’s coverage of the UK elections in July, I was struck by the contributions of one of the grizzled emeriti on the panel, talking like a Welsh snapping turtle about how “repulsive” George Galloway was back in Parliament in the 1980s. It was Neil Kinnock, born the same year as Joe Biden, and still able to give a few pointers if the president had cared to watch.

His valedictory address to the Democratic National Convention on Monday was, I thought, a rather unfitting end to this unexpected third act. He was loud and forceful, clearly and genuinely angry about Donald Trump and defiantly eager to defend his own record. But the strain of the years could be heard in the labored pacing and the absence of wistful charm about Scranton and his dad saying things like “Joey, we have to move to Wilmington but everything’s gonna be alright.” It was good that he had the chance to enjoy the admiration of his party, even if much of that admiration, he must have known, was relief at his decision to yield the nomination. And it would take uncommon personal virtue to, in addition, yield the opportunity to make the case for himself one last time, to give a lightly-edited version of the acceptance speech he’d planned to give. But it would have been better—more useful to his party and better for his own legacy—to tap into the expansive, generous, patriotic mode that literally standing down as your party’s nominee opens up for you. An affectionate look back on how America has changed for the better over a long life of public service, and a hopeful look forward at the accomplishments available to his successor. One might have enjoyed some bittersweetness, some nostalgia, but as the 48 minutes of the speech wore on, I could only feel relief that it was almost over.

Donald Trump, too, is not what he was. A failed real estate mogul, marketer of fake airlines, football leagues, and universities, and reality star on the wane, he also managed to find his voice in an unexpected venue. Lacking any qualifications in the ordinary sense, and giving no indication of civic or personal virtue, he was good on stage. In the 2015 and 2016 primary field, he was like a knuckleball pitcher, throwing shaky, unlovely material out there that no one had a way to hit. His instincts, both for desires of the median Republican voter and for the vulnerabilities of his opponents, were nearly flawless. His victory in 2016 was a fluke, undoubtedly attributable to the last-minute Comey letter, but he was only an October surprise away from winning thanks to a canniness as a performer that neither party had managed to disable. Once he had the job, in a way, it was all downhill. He couldn’t run the West Wing, couldn’t talk about policy, couldn’t function at all apart from an audience to rile up. His one big legislative success was a large tax cut that polled badly.

Now even the old fluency has clearly started to flag. He can still talk fast, and from time to time he sticks to a script with strong themes, but in the debate he repeatedly rambled off into the wilderness of MAGA mythology. Against anyone else, it would have been comprehensively viewed as a bad performance. And since then, he’s only gotten worse. Not long ago he was a poor man’s Don Rickles, hurling insults and nicknames and riffing entertainingly on whatever topic came up. Now he’s becoming the utterly destitute man’s Fidel Castro, tormenting his audiences with 90-minute monologues that have no form or obvious purpose.

It was remarked over and over that these were the two oldest candidates for president ever in our history. And they both showed their age in different ways. But the problems were never strictly, so to say, operational. They had started to give the appearance of material running out; of two men who were meant to be secondary players, “fifth business,” unaccountably thrust into the starring role with a half-written script. Their successors, real and imagined, underline their anachronism. In Vance, Trump has chosen from one set of would-be heirs, the extremely online oddballs who speak exclusively but awkwardly in the new MAGA dialect (DeSantis, Ramaswamy); the other set is the people who are genuinely hapless (MTG, his children). Biden is, as his biographer calls him, “the last politician,” the only active link to the days of the New Deal coalition, the last Democrat elected before the Watergate Babies (Bernie Sanders, roughly Biden’s age, was elected to the U.S. House in 1990, on the same day Biden was elected to his fourth term in the Senate). In Harris, the Democrats have a competent standard bearer whose gifts, and whose inarguable availability, have been enough to defer the faction fighting between professional-class progressives and professional-class moderates that seemed inevitable once the party was out of Biden’s shadow. Ezra Klein made the case on Tuesday that the Democratic Party in 2024 is the creation of Joe Biden, through his personal fusion of a moderate, old-time standard bearer with personnel who came largely from the Sanders-Warren faction and a renewed embrace of organized labor. But of course, something very similar could have been said of Barack Obama at the 2016 convention, after twice carrying Iowa, Ohio, and Florida and seeming to have the “new coalition” firmly in place and poised for long-term electoral success.

This is a tasteless and trivializing way to talk about the most powerful office in human history, which is not a part in a play at all but a real thing that hurts and helps real people. But this is exactly the problem: we don’t seem to interact with it that way, not anymore. Politics isn’t a story with characters, but it is a spectacle. Two unsuitable, unpopular men, their resentment and delusion of indispensability on full display, tottering atop once-great political parties who seemed incapable of doing any better, suggested the possibility that maybe we really do want this, after all. One party took the script out of the lead’s hands, the other decided that it was more than content to let the show go on. And that’s unfortunate, because if there has been one undeniable upside to the last few weeks as a politics news super-consumer, it has been the mere irrefutable fact of newness.

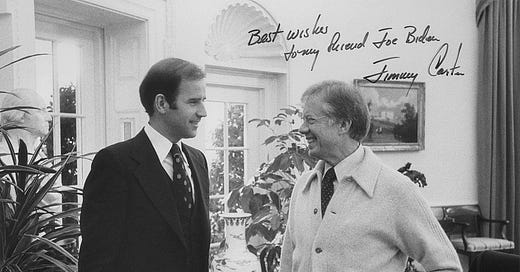

But as Biden departs center stage, I think it’s worth lingering on the obscure appeal of this odd rivalry. As long as Joe Biden and Donald Trump are on the scene, the style and mannerisms of their mostly vanished worlds are still alive. Trump is fond of saying that people look like they come “from central casting,” a show business idiom that has to be decades out of date by now. But it’s one my parents used, so I grew up with it. Biden accused his vice presidential opponents of trading in “malarkey,” a word so incongruously old-timey that it became a calling card. At the debate, he bestirred himself to accuse Trump of having the “morals of an alley cat.” As long as people in public life talk like that, the world of my grandparents isn’t totally dead. He told stories about his father and mother; who wouldn’t wish to be remembered like that, on such a stage? Who wouldn’t love to have someone to remember in just that way?

Our culture has become eerily nostalgic. The Know Your Enemy guys talk fondly about big-city machines and the Mafia (but leftistly). Conventions brokered by governors, party bosses, and union bigwigs are back in vogue. I don’t have any idea what Delaware politics looked like in 1972 but I picture union hall dinners with lots of smoke and people being overserved and back-slapping and the like. I don’t know anything about trying to get into Manhattan real estate in the 1980s but Americans can’t resist stories about the web of mob-connected graft that held construction, like so much else in the city. Do we actually think the 70s and 80s were better than our own time? I doubt it. But somehow we miss them, even if we only experienced them second-hand. The next Republican standard bearer, whoever that is—and whenever, because Trump will be the nominee every four years as long as he lives, 22nd amendment be damned—will likely have grown up on the internet.

It was, in the end, good and smart of Biden to make that last clean contrast with the person whose political career will be mutually defining with his. Eventually every poor player’s hour of strutting and fretting is up, and it’s better to exit to cheers than stony silence or, worse, a violent mob acting on your behalf. But while it has become fashionably fatalistic or cynical to attribute the deranging vagaries of recent American life to “the writers,” I think that’s actually what we need. Time was, a future president could absorb the oral history, the idioms, the patois of their world in their sleep. New players will need new material.